How to solve the fusion fuel puzzle?

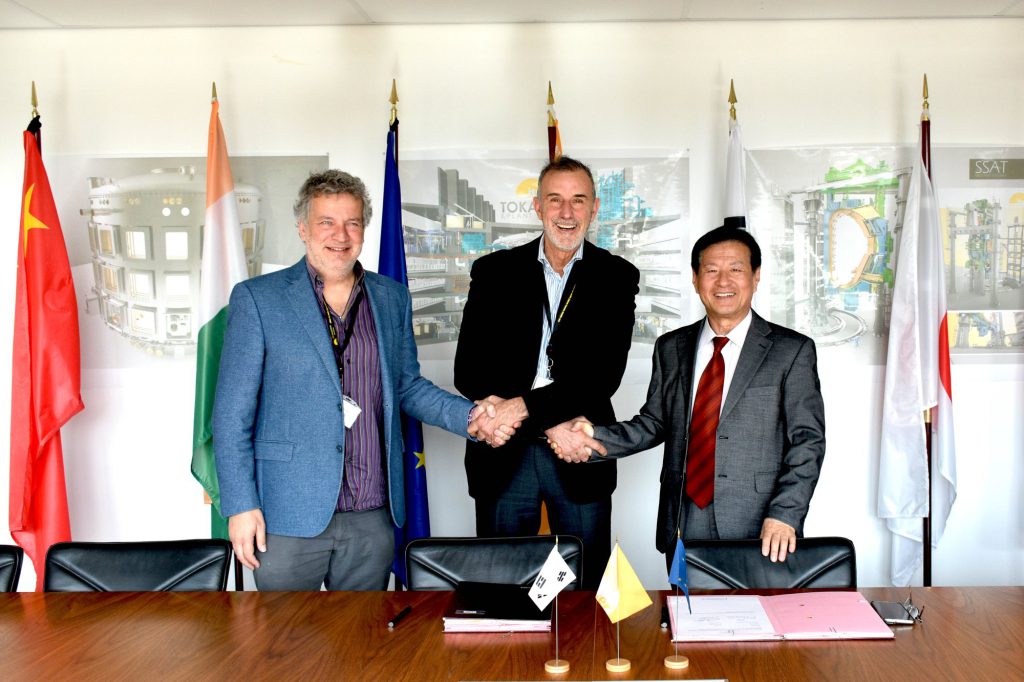

Front row (L-R) Jean-Marc Filhol, F4E Acting Director, signing one behalf of Europe the Partnership Arrangement, with Kijung Jung, ITER Korea Director-General. They are joined by colleagues from F4E, ITER Organization, ITER Korea directly involved in this achievement. March 2023, Cadarache, France. © ITER Organization

Fusion has often been described as the holy grail of energy precisely because it comes with considerable advantages such as no greenhouse gas emissions, inherent safety, sustainable waste management and abundant fuel. The physics behind a fusion reaction is relatively straightforward. We need two hydrogen isotopes: Deuterium, available in sea water, and Tritium. The latter, however, is harder to get in nature and in the case of ITER, it will be purchased from the fission industry, as the quantity required is little. But if in our future energy scenarios, we expect fusion to play a role in power supply, then how we can produce tritium in a self-sufficient manner to fulfill larger needs? These are some of the strategic considerations steering investment in Test Blanket Modules (TBMs). And what if we could find a way to breed tritium inside the reactor, say for instance in a “box”, that would regenerate enough of it on a steady basis? That’s a simplified version of the TBMs mission. They rely on the assumption that when fusion neutrons impact lithium, they produce tritium. ITER will provide the scientific community with a one-of-a-kind opportunity to test simultaneously four tritium breeder concepts. The lessons learned will feed into future fusion reactors, which will be connected to the grid.

The four TBMs concepts are in development by four different ITER parties: a water-cooled lithium led by Europe, a water-cooled ceramic by Japan, a helium-cooled ceramic by China, and a helium-cooled ceramic developed now jointly by Europe and Korea. Science diplomacy has proved to be an extremely successful mechanism in bringing countries together around the same table, regardless of distinct commercial interests. Such high-level agreements help parties to exchange information, put best practice at work, and gain insight. These are also the foundations underpinning the Partnership Arrangement between Europe and Korea, signed earlier this month, together with an Arrangement signed between the two parties and ITER Organization.

The timing of all this could not have been better, as closer collaboration is one of the priorities of Pietro Barabaschi, Director-General of ITER Organization, aiming to bring teams closer together and to capitalise on their talent. This important milestone for the European and Korean teams of the TBMs came after three years of work behind the scenes when in 2020, the European Commission and the Korean Ministry of Science and ICT started to explore ways of developing jointly a helium-cooled ceramic breeder TBM system. A year later, a task force was created holding technical discussions on planning, distribution of workload, questions linked to quality assurance and intellectual property, amongst other topics. The talks resulted into legal documents that were finalised towards the end of 2022. The thrust of these documents was that the two partners were more than just co-financing pieces of equipment, they were co-designing and co-producing a complex experimental system. The partnership, which is expected to run until 2042, sets Korea as a leader of the work conducted, making an in-kind contribution up to 60% with the remaining 40% for Europe. The delivery of the joint TBM, and its ancillary systems, is planned for 2031. The design of this joint TBM system will follow closely that of Europe’s, and the steel to be used will be Europe’s preferred choice-Eurofer97.

“This signature marks the end of a long negotiation for many of you. But most importantly it now triggers the start of design, construction and procurement activities between the Korean and European TBM colleagues, in a fully integrated single project team, in anticipation of the integration that the Director-General of ITER Organization is promoting for the ITER project,” explained Jean-Marc Filhol, F4E Acting Director.

“F4E has been working hard over the last years with our partners from Korea, to develop a partnership that is solid in all dimensions. Our collaboration runs deeper than the drafted legal text. We learned how to work trustfully with one another,” said Yves Poitevin, F4E TBM Programme Manager. “Also, the teamwork in F4E, across our departments and services, was excellent. We worked for the same objective, in an extremely collegial manner, capitalising on the expertise of each contributor,” adds Szymon Wesolowski, F4E’s Legal Officer supporting the negotiations.

Through this collaboration, there is hope that technical experts will be able to resolve one of fusion’s long-standing conundrums linked to its fuel. By using ITER as a test environment, Europe and Korea will finetune one of the four different alternatives. But more importantly, they will be able to gain further insight, and equip tomorrow’s fusion devices with fuel supply that will be safe and self-sustained.